The American Plate: a Culinary History in 100 Bites by Libby H. O'Connell

This is a really interesting book and a unique way to look at American history through food. The author breaks down the history of America into 100 "bites" and each chapter (with 10 bites each) covers a specific time period in history. It's obvious that as technology changed so did food/cooking, but it's really interesting to see incremental changes throughout the book leading to things we're familiar with today. The author also intersperses the book with lots of recipes - some include both the "original" recipe and an "updated" one more applicable for today. Some of the recipes are very familiar like Brunswick Stew or Baked Alaska, while some others are not as recognizable today like Roast Beaver Tail and Syllabub. Overall, this is a really interesting book that gives an overall history of our country through our food.

Traditions tend to be traditions for a reason, but we aren't great at remembering that - especially when it comes to food. Some interesting quotes:

"About 3500 years ago, native people in Mesoamerica developed a process called nixtamalization that improved the food value of maize...They soaked the hard-shelled corn in water mixed with wood ashes or lime overnight. The softened hulls floated to the top of the water or were easily slipped off by hand...But nixtamalizing the tough, dried kernals made their food value, including niacin, become much more accessible to the human gut...Later, European settlers would skip this step in corn preparation because their millstones were powerful enough to turn corn into meal without soaking it. Unfortunately, that meant that their systems did not absorb all the nutrients from the maize. Thus, lacking nixtamalization as a culinary tradition, settlers with highly corn-dependent diets sometimes ended up with severe niacin deficiencies that caused diseases like pellagra." (p.5)

"Most families baked bread at home or bought it from small, local bakeries. Eventually, urban ethnic enclaves included bakeries that sold breads with similar aromas and appearances to those in the old country, although the flour was not always the same. All bread was artisanal: if not homemade, it was handmade. That is, until the 1890's, when factory-made bread became more available. In contrast to today's perceptions about whole-grain, handmade bread, factory-made loaves held the reputation of being healthier and more sanitary for decades because they were made of that oh-so-desirable refined flour, with dough kneaded by machines. People wanted clean bread that wasn't tainted by human touch. Bit by bit, industrially produced bread edged out home or locally baked bread...The new white bread represented not only convenience but the modern American way. The same reformers who urged the passage of the Pure Food and Drug Act campaigned against 'squalid' immigrant bakeries with 'unscientific' techniques...Soldiers drafted for World War II manifested vitamin deficiencies because they were no longer getting the nutrients needed, even though they ate more bread than ever before. Alarmed by the increase of nutritional diseases like beriberi and pellagra, the federal government encouraged the enrichment of white bread with vitamins and minerals similar to those found naturally in whole grain bread." (p. 263-4)

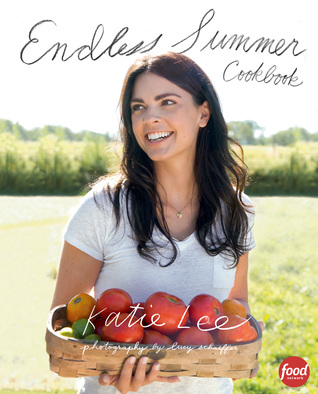

50 Children by Steven Pressman

In early 1939 Gil and Eleanor Kraus were a non-religious Jewish couple living in the Philadelphia area. When they started hearing about the persecution of Jews in Europe they were concerned, but as things became worse in Europe they were two of very few civilians who felt compelled to do something tangible. Gil was a successful lawyer and also volunteered for Brith Sholom, a Jewish organization he belonged to. When the leader of their local Brith Sholom chapter asked Gil to help rescue Jewish children and bring them to America - he didn't hesitate to say yes. He was able to quickly get Eleanor on board and they started working through the difficult and red-tape strewn process. Because of Gil's skill as a lawyer and his connections to some helpful government officials, the couple was able to successfully bring 50 Jewish children from Nazi Germany to America. Almost unbelievably, many of the children were reunited with their parents within a few years. While this book is non-fiction, Gil and Eleanor's story is so hard to believe that it almost reads like fiction. While researching this book the author was able to find 37 of the 50 children rescued by Gil and Eleanor - about half of that 37 had passed away, but he was still able to find out what their life was like after the rescue. While many people did help Jewish families during the Holocaust, many of their stories are lost as they may have also died during WWII or they simply didn't feel the need to tell their stories to future generations. Thankfully Eleanor kept a diary during their time working on this project and she also had written an unpublished memoir about their work. Otherwise, we might have never known their story. A very inspirational and amazing story.

Two of the things that really amazed me in this book was 1)how unfeeling and unhelpful the US government was about the plight of the Jews in Europe. President Roosevelt could have worked to relax the US's strict immigration laws, but we chose not to. Most likely because of wide-spread public anti-Semitism that would have turned public opinion against the President. And 2)how the other Jewish aid organizations responded to the Krauses work with Brith Sholom. Instead of trying to help them, the other organizations who were also trying to rescue European Jews seemed jealous and actually tried to stop their work! Wasn't the goal to help the European Jews, not make your organization look the best?! Obviously, hind sight is 20/20, but this information was pretty appalling.

Some quotes I liked:

"Eleanor was painfully conscious of her role in the tragic circumstances that led parents to willingly offer up their children. 'To take a child from its mother seemed to be the lowest thing a human being could do. Yet it was as if we had drawn up in a lifeboat in a most turbulent sea,' she wrote. 'Each parent seemed to say,'Here, yes, freely, gladly, take my child to a safer shore.' Fifty times this question was asked, 'Will you leave your mama and papa and come to America with us?' And each time the question was asked, I died a little more.'"(p. 148)

"...Jews were not allowed to give the Nazi salute. The parents risked being arrested if they raised their arms to wave good-bye. They stood along the platform, staring in silence at their children through the train's glass windowpanes...Finally the train sounded a piercing whistle as it slowly edged its way out of the station. Eleanor, surrounded by several of the children, peered out the window as the platform gradually receded from view. 'The parents stood in completely orderly and quiet fashion. Their eyes were fixed on the faces of their children,' she wrote. 'Their mouths were smiling. But their eyes were red and strained. No one waved. It was the most heartbreaking show of dignity and bravery I had ever witnessed.'"(p. 176-7)

"The Associated Press dispatch from Havana described a tense saga over the fate of 937 Jewish passengers who had sailed from Hamburg...Although the Jewish passengers on the St. Louis had obtained visas to enter Cuba, by the time the ship arrived in Havana on May 27, government officials had changed their minds about honoring the visas...American officials, including President Roosevelt, received a flood of urgent requests to allow the St. Louis into the United States...The appeals fell on deaf ears. Even as the ship sailed within sight of the United States - at one point, passengers could see the lights of Miami from the deck of their doomed ship - American officials refused to relax the laws that stood between the passengers and freedom...four other European countries [decided] to issue entry visas for the passengers. Among those, 288 were allowed into Great Britain and 224 were admitted into France. Belgium took in 214, the Netherlands 181. For many, sadly, the reprieve proved to be temporary. Of the 937 passengers who first set out for Cuba, 254 lost their lives in the Holocaust - victims of roundups and deportations that came in the wake of the Nazi occupation of Belgium, Holland, and France." (p. 210-11)

"Between 1933 and 1945, the United States admitted between 1,000 and 1,200 'unaccompanied' Jewish children - children traveling without their parents - into the country. The fifty children rescued by Gilbert and Eleanor Kraus accounted for the largest known single group to be admitted into America during the entirety of the Holocaust. And while the United States opened its doors to 200,000 European refugees - mostly Jews - during Hitler's murderous reign, the sad fact remains that hundreds of thousands of additional lives lost in the ashes of the Holocaust might well have been saved had American been more generous. Among the victims of the Nazis' Final Solution were one and a half million children." (p. 232)

"For anyone who believes that the Holocaust was foreign and not American history, this story reveals multiple ways in which the United States was implicated in shaping the fate of European Jewry during the 1930s and 1940s. American isolationism and widespread anti-Semitism made it impossible to craft public policies that might have been more compassionate toward refugees and led the American Jewish community, fearing a backlash, to be exceedingly cautious in advocating on behalf of European Jewry." (p. 254)

"...the Krauses were not intelligence agents privy to classified information. They were reading the newspapers after Kristallnacht and learning of the brutality with which Jews were being treated in Vienna and across Germany. What distinguished them from others is simply that they chose not to close their eyes to what they were reading. In 1938-1939 information regarding Germany's treatment of Jews was publicly available to all Americans. Recent research and the opening of formerly classified American wartime archival documentation have also made it clear how much information American policymakers had regarding the mass killing of Jews that began after the outbreak of war in September 1939." (p. 256)

The Year of Reading Dangerously by Andy Miller

After he had a child and began approaching the age of 40, Andy Miller decided to return to his childhood love of reading. He created a List of Betterment with titles that he had always claimed to have read, but actually had not. It was mostly classics and literary fiction. Shortly after beginning he remembered how much he LOVED reading and wondered why he had ever stopped! While I did like this book and actually laughed out loud a few times while reading it, I didn't love his writing style. It was kind of all over the place and often had random thoughts thrown in and lots of footnotes too. But, I have never read anything like the chapter where he compares Dan Brown's The Da Vinci Codewith Herman Melville's Moby-Dick - it was awesome and hilarious! Overall, an interesting read for any book lovers, especially if you like creating and/or reading from lists.

Some quotes I liked:

"Whereas on a commuter train, though you are physically in it together, you are trying forcefully to pretend otherwise. It is not a crowd in which one disappears but a gang of individuals in noisy denial - tish, honk, bing-bong, WAAAAAAAAAAH. Hell is other people, said Jean-Paul Sartre. Don't take this the wrong way, but I think he means you." (p. 91)

"Notorious Middlemarch-shirker Salman Rushdie has describedThe Da Vinci Code as 'a novel so bad that it gives bad novels a bad name'. None of which has prevented Dan Brown becoming one of the most widely read authors of modern times. Only E.L. James, author of Fifty Shades of Grey and its sequels, comes close. On average, everyone has read The Da Vinci Code. You have probably read it. Even if you have not read it, statistically you have." (p. 101)

"For a period in the mid-1930s, between more anthropologically prestigious engagements, George Orwell worked in a bookshop. He tired of it quickly...'The thing that chiefly struck me was the rarity of really bookish people. Our shop had an exceptionally interesting stock, yet I doubt whether ten percent of our customers knew a good book from a bad one...Many of the people who came to us were of the kind who would be a nuisance anywhere but have special opportunities in a bookshop.'." (p. 141) - I think this can most definitely apply to the public library from my personal experience!

"But then I had to go to school, the catastrophe of my childhood. I stood in the playground on the very first morning, while all around children ran and shrieked and laughed, and though I did not yet know the word, I thought to myself: oh shit oh shit oh shit. And these first impressions proved to be correct. There was not a single school day for the next thirteen years when I did not think: oh shit. From the moment I arrived, I was waiting to leave. Books became more important to me then." (p. 169)

"I came to the conclusion that I was probably not cut out for the reading group experience...I did not reach this conclusion immediately and it may surprise the reader to learn that I remained a proud Spartan [the name of his book club] for almost three years, longer than some marriages, though no less bloody. There were happy times. There were bad patches...But the truth is I never once changed my mind about a book because of anything said in one of our meetings. I looked at Cakes and Aleagain before writing this chapter. I still think it's rotten." (p. 209-10)

Missoula: Rape and the Justice System in a College Town by Jon Krakauer

This is the most disturbing book I have EVER read, but it should also be required reading for EVERYONE! Jon Krakauer examines the disturbingly high incidents of rape in our country by closely examining 3 cases that happened in Missoula, Montana. While these cases are part of a larger investigation into sexual assaults in Missoula, they could have happened anywhere. This book is microcosm of a much, much larger problem that is rarely discussed so openly. Of the 3 main cases that Krakauer follows 2 of the cases were prosecuted with one accepting a plea agreement and the other resulting in an aquittal and the 3rd was declined to be prosecuted by the District Attorney's office, but did result in a University noncriminal judicial decision to expel the rapist. All 3 of these women were put through unimaginable hell - not just by their rapists, but also by police and investigators who routinely minimized their ordeal and forced them to feel like victims all over again.

The two most disturbing things about this book are 1) the unbelievable rape statistics (which I'll quote below) and 2) how ALL of the rapists in this book still feel like they did nothing wrong. Krakauer briefly mentions how pornography has shaped (and in my opinion destroyed) these men's views of sex and women. My opinion is that this generation - today's college students and younger - who have grown up with unprecedented access to hardcore pornography via the internet will be just the tip of the iceberg of sexual violence and dysfunction. This book should scare the hell out of you. And in the words of Jon Krakauer in an interview about this book: "If you're not a feminist, then you're a problem." I might have to get that quote printed on a shirt! Krakauer does an incredible job with this book and handles an emotional and horrific problem with grace and skill. This is a very hard and disturbing book to read, but it is a must-read.

Quotes I really liked:

"As Kaitlynn Kelly listened to Pabst tell the court that Calvin Smith was too kind and compassionate to be a rapist, she was dumbfounded. 'Kirsten Pabst refused to even talk to me when I was trying to find out why nothing was being done about my case,' Kelly recalled bitterly. 'And then she goes out of her way to show up at University Court to testify for the asshole who raped me? I couldn't believe it.'"(p. 91)

"Kevin Barrett criticized both the police and the prosecutors in Missoula for their apparent reluctance to pursue rape cases unless they were absolutely certain they would prevail in court. He pointed out that in the decades before cops and district attorneys had the technological means to use DNA as evidence, 'every rape case was a matter of 'he said, she said.' But we still prosecuted...Everybody likes to have a high batting average when it comes to winning cases. But sometimes you have to bring a case to court and let it be decided there, instead of deciding beforehand that the odds of winning aren't good enough to go forward. When you have a victim who is willing to go the distance and you shut her down, what does that say to other victims? 'Don't bother?' When cops and prosecutors fail to aggressively pursue sexual-assault cases, Kevin argued, it sends a message to sexual predators that women are fair game and can be raped with impunity." (p. 103)

"Rape is the most underreported serious crime in the nation. Carefully conducted studies consistently indicate that at least 80 percent of rapes are never disclosed to law enforcement agencies. Analysis published in 2012...suggests that only between 5 percent and 20 percent of forcible rapes in the United States are reported to the police; a paltry 0.4 percent to 5.4 percent of rapes are ever prosecuted; and just 0.2 percent to 2.8 percent of forcible rapes culminate in a conviction that includes any time in jail for the assailant. Here's another way to think about these numbers: When an individual is raped in this country, more than 90 percent of the time the rapist gets away with the crime." (p. 110)

"Research by David Lisak suggests that Barrett's and Kelly's concerns about their assailants [being repeat offenders] are not unfounded...[In a] study, titled 'Repeat Rape and Multiple Offending Among Undetected Rapists,' co-authored by Paul M. Miller and published in 2002, added significantly to the understanding of men who rape. Lisak and Miller examined a random sample of 1,882 men, all of whom were students at the University of Massachusetts Boston between 1991 and 1998. Their average age was twenty-four. Of these 1,882 students, 120 individuals - 6.4 percent of the sample - were identified as rapists, which wasn't a surprising proportion. But 76 of the 120 - 63 percent of the undetected student rapists, amounting to 4 percent of the overall sample - turned out to be repeat offenders who were collectively responsible for at least 439 rapes, an average of nearly 6 assaults per rapist. A very small number of men in the population, in other words, had raped a great many women with utter impunity...A similar study published in 2009 by Stephanie K. McWhorter, which examined 1,149 navy recruits who'd never been convicted of sexual assault, replicated Lisak's findings: 144 of the recruits (13 percent) turned out to be undetected rapists, and 71 percent of those 144 rapists were repeat offenders...It should be noted that all of the subjects in the studies by Lisak and McWhorter participated voluntarily and that none of the undetected rapists identified by the researchers considered themselves rapists...The participants in the study had no qualms about being research subjects, Lisak told me, 'because they share this common idea that a rapist is a guy in a ski mask, wielding a knife, who drags women into the bushes. But these undetected rapists don't wear masks or wield knives or drag women into the bushes. So they had absolutely no sense of themselves as rapists and were only too happy to talk about their sexual behaviors.'" (p. 116-8)

"On May 1, 2012, the assistant attorney general for the Civil Rights Division of the U.S. Department of Justice, Thomas Perez, arrived in Missoula and held a press conference to announce that the DOJ had launched a major investigation into the handling of eighty Missoula sexual-assault cases over the previous three years. Perez said the DOJ would be investigating the Missoula County Attorney's Office, the Missoula Police Department, and the University of Montana." (p. 148)

"When the DOJ had announced its investigation in May 2012, it had noted that at least eighty alleged rapes had been reported in Missoula over the preceding three years. But the findings sent to Van Valkenburg in February 2014 revealed that there were actually 350 sexual assaults reported to the Missoula police between January 2008 and May 2012, a span of fifty-two months...The report warned, 'Since the majority of sexual assaults are committed by repeat offenders,' the effect of the MCAO's failure to file charges was compromising 'the safety of women in the Missoula community as a whole,' because 'perpetrators who escape prosecution remain in the community to reoffend.'" (p. 325-7)

"The DOJ investigation identified 350 sexual assaults of women that were reported to the Missoula police during the fifty-two months from January 2008 to May 2012. The Bureau of Justice Statistics estimated that in 2010, the annual rate of sexual assaults of women in cities with populations under 100,000 was 0.27 percent, which for Missoula equates to 90 female victims per year, of 390 over a period of fifty-two months. This suggests that, rather than being the nation's rape capital, Missoula had an incidence of sexual assault that was in fact slightly less than the national average. That's the real scandal." (p. 340-1)

The Nourishing Homestead by Ben Hewitt

With every book by Ben Hewitt I read I love him even more! InThe Nourishing Homestead Hewitt goes into great detail about his family's 40 acre "practiculture" homestead - what they grow and raise, how and when the built the various structures, tips on raising livestock, how they involve their children, and much, much more. While some of the information is more obviously geared toward someone trying to build their own homestead, much of it could be applied to anyone who's interested in more homemade/homegrown lifestyle. This book more so than any of his others reminds me of Joel Salatin because Hewitt explains at length the importance of nourishing the soil in order to grow the most nutrient-dense vegetables and animals. Overall, if you are in any way interested in growing and/or raising more of your own food there will be something (if not LOTS of things) in this book that will help you. I would highly recommend this one and may end up buying it for myself!

Here are some quotes I really liked:

"The term practiculture evolved out of our struggle to find a concise way to describe our work with this land. Of course, no single word or term can fully explain what we do...The longer I do this work, the less I feel as if we are practicing agriculture so much as we are simply practicing culture. Practiculture also refers to our belief that growing and processing our food, as well as the other essentials necessary to our good health, should be both affordable and, for lack of a better term, doable. Practical. It should make sense, not according to the flawed logic of the commodity marketplace, which is always trying to convince us that doing for ourselves is impractical, but according to our self-defined logic that grasps the true value of real food to body, mind, spirit, and soil. Finally, practiculture is about learning practical life skills and the gratification that comes from applying those skills in ways that benefit one's self and community. This sort of localized, land-based knowledge is rapidly disappearing from first-world countries in large part because the centers of profit and industry would rather we not possess it. They know that its absence makes us increasingly dependent on their offerings." (p. 27)

"Obviously, I like making butter. But the moment I begin to apply the mentality of money to the process my fondness for the task begins to fray. Because let's be honest: It makes no fiscal sense...when I take measure of the time and inputs, and I consider that time and those inputs to be of monetary value...I begin to view my butter in a different light. I begin to see how perhaps it would make more sense to simply sell the time it takes to make my butter and to buy butter on the open market, where it goes for a fraction of the price mine embodies...as soon as I start thinking in these terms, butter making begins to feel like a burden, rather than a joy...This stinginess is a learned response, the result of an economy that depends on consumption rather than production, and I am struck by how markedly things have changed in a relatively scant amount of time. Less than a century ago, even the poorest Americans had access to fresh butter and other unadulterated, nutrient-dense foods. But the advent of modern food regulations and technologies (in the case of dairy, pasteurization) has ensured that none but the fortunate few will ever know what real butter tastes like. None but the fortunate few will ever know the pleasure of churning their own. For everyone else, it is too time consuming and troublesome. Or simply too expensive. It is infuriating that we have arrived at a place where the fundamental right to feed ourselves as we wish has been largely eroded. At this very moment, I could leave my house, drive a handful of miles, and purchase a semiautomatic handgun, a carton of unfiltered cigarettes, and a fifth of whiskey. Yet I can't legally sell the butter I make at any price. I can't legally sell a home-butchered hog or even a single link of the excellent (if I do say so myself) sausage we make. The reason for this is simple: When I buy whiskey, cigarettes, and firearms, the rich get richer. When I sell a pound of butter or a package of sausage, they get a little poorer." (p. 40-41)

"It is always easiest to do what everyone else is doing. And then I remind myself: Easiest, yes. But not necessarily the most satisfying or correct." (p. 44)

"Consuming nutrient-dense foods will provide us with the foundation of deep nutrition that should allow us to escape many of the assumed degenerative diseases of modern first-world societies. It's worth noting that many of the diseases and conditions we currently accept as almost inevitable hardly existed only a century ago. Heart disease, cancer, diabetes, and the innumerable other side effects of industrialization are notinevitable." (p. 72)

"In short, here's how it works: The food and drug industries, aided and abetted by governmental agencies funded by our tax dollars, have entered into a symbiotic and highly profitable relationship. One industry feeds us the garbage that makes us sick, while the other stuffs us with the pills that keep us alive so we can keep eating the garbage that's making us sick, therefore necessitating the pills that allow us to live. Meanwhile, the governmental agencies that regulate these industries continually enact regulation that is favorable to these industries and detrimental to truly nutritive, small-scale food production. And the whole time, our need for constant medical attention ensures that we never stray too far from the meaningless, make-work careers that provide the health insurance we could no longer afford if we dared pursue our true passions and interests." (p. 77)

"One of the most profound but least discussed changes in the American diet over the past century is the reduction in the diversity and quantity of bacteria contained in our food. This reduction correlates to the expansion of an industrialized food system that, for a multitude of reasons, cannot produce bacterially diverse products. In part, this is because the conditions that promote the growth of beneficial bacteria can also support harmful bacteria, and it's also because modern distribution systems are unable to accommodate 'living' foods. Likewise, overblown fears of foodborne illness have created a regulatory system that makes many of the healthiest, most biologically diverse foods flat-out illegal. The hard truth is this: Many of the healthiest foods - such as raw butter and raw fermented dairy products - cannot be purchased at any price." (p. 89-90)

"Farmers have been safely and humanely slaughtering and processing animals on farm for literally centuries, both for their own families and for others in their community. The advent of contemporary food regulations has little to do with legitimate fears over foodborne illness and everything to do with suppression and control. These regulations are largely why it is so difficult to create a viable local food-based business." (p. 224)

Picnic in Provence by Elizabeth Bard

I remembered reading Bard's previous book Lunch in Paris, but I didn't remember much of the details. So, Picnic in Provencepicks up with Elizabeth and Gwendal expecting their first child. On a trip to Provence before the baby arrives they fall in love with the small town of Cereste and impulsively decide to move there after the baby is born. It's almost a year before they fully move there, but once they settle in they love their small community. And of course most of the story centers around local food and Bard ends each chapter with 2 or 3 recipes of food mentioned in that chapter. In the end they decide to open an artisanal ice cream shop with seasonal, local flavors. The second half of the book is about their journey into the ice cream business. While I didn't LOVE this book, it was an overall nice, easy read. It does make you think about the idea of moving to a small town/rural area and living a more modest (and hopefully happier) lifestyle.

Eating Dangerously by Michael Booth and Jennifer Brown

DON'T WASTE YOUR TIME WITH THIS BOOK!!! There are SO many other MUCH better books that talk about the evils and perils of our current industrial food system. If you want to read more about how to eat better, healthier, real food I suggest reading Joel Salatin, Ben Hewitt, and many others who are farming in smaller-scale, sustainable ways. By the end of this book I was so mad at the misinformation and lack of helpful options. The first half of the book talks about recent outbreaks of food-borne illnesses and why these things happen - basically it's a product of the industrial food system (which I agree with completely). Then the second half of the book talks about ways you can be safer and with your food - this is where I start to get mad. Basically the authors seem to be suggesting that you're better off eating processed food full of who knows what because most food-borne illness outbreaks are related to fresh food (hamburger meat, cantaloupe, spinach). They also say that if you shop at farmer's markets you're just "romanticising" your food and it's not any better for you or safer. That is bullshit! When you KNOW your farmer and you've visited their farm you KNOW your food. That is not the case with ANYTHING you purchase at the grocery store. I know that there might be shady "farmers" at some markets that don't grow their own food, etc. but that's why it's so important to get to know them and visit their farms so you can see first hand how they are raising their animals or crops. The authors also imply that many people think if they buy from the farmer's market they don't need to wash the veggies or cook the meat - I mean what kind of dumb asses are these people talking to?! NO ONE at a decent farmer's market would EVER suggest that you don't follow basic kitchen/cooking safety guidelines! Basically this book scares the hell out of you with horror stories of food poisoning outbreaks (which are true and are scary), but then their solutions are to either eat processed food or just wait until you get one of the many food-borne illnesses out there. They even have a chapter on the most common ones and what the symptoms are so you can self-diagnose WHEN not IF you get one!

I am NOT a fan of the industrial food system, but this book is a joke as far as "helping" anyone. If you are afraid of the industrial food nightmare (and you should be), the answer is to opt out by knowing your local farmers, growing some of your own food, and cooking local foods at home (safely of course). Don't waste your time reading this joke of a book. I can't remember the last time a book made me as mad as this one did. Here are a few of the worst quotes:

"Which is better to feed your kids for lunch: processed chicken nuggets from the freezer section or a burger made from ground turkey? The answer depends on whether you are more worried about feeding the children nitrates, sodium, and saturated fat or reducing the risk of ingesting illness-inducing Salmonella orCampylobacter. (p. 91) REALLY?! Those are your ONLY food options?! Processed shit or real shit in your meat - this is one of the most offensive sentences I've EVER read!

"It's all the rage to buy farm-fresh food, to seek out free-range eggs and organic vegetables delivered to the door or grown in the backyard. That's all great - but don't take the back-to-nature way of life all the way to raw milk. It's not worth it. 'Raw milk is horrifically dangerous. I would never advise anyone under any circumstances to drink it,' said Klein, with the Center for Science in the Public Interest." (p. 95) So now eating local, whole foods including raw milk which people have consumed for centuries, is now just a "trend" that will die off when all the raw milkers die from food poisoning - give me a break!

"Stroll through the farmers' market each week, sampling watermelon and homemade sausages and loaves of bread full of hearty seeds and grains. Go ahead - these are all wonderful ways to live. You'll develop a greater appreciation for the people who raise our food and, at the same time, help bolster the local economy. But while you are doing all this, don't be naive enough to assume you are less likely than traditional grocery store shoppers to pick up a dangerous food pathogen along the way. Eating healthy, or organically, or locally, has its benefits - few pesticides, more humane treatment of animals, less fossil fuel burned to transport the bananas from Chile or the hamburger from who knows where - but it has not been found to reduce the risk of foodborne illness." (p. 137) In my opinion this is just a flat out lie. There is no way that eating locally grown and humanely raised food is as dangerous as industrially produced food.

"Echoed egg expert Jay-Russell: 'There is a lot of naivete going on as people go back to the locavore. There is a romanticism that doesn't appreciate the risks'." (p. 149) The risks with food are from the industrial system and no amount of laws or incentives to those companies will ever fix that. Food was never meant to be produced on the scale that it is now and that is why the industrial food system will NEVER work. This sentence is on the last page of the book and I just wanted to throw this book at Jay-Russell AND the authors!